Korean and Japanese: which of these languages is easier to learn?

For many native English speakers, the allure of the Far East and its cultures is often accompanied by the widely held belief that learning any of their languages - such as Japanese and Korean - is extremely difficult.

While the ability to learn any language is limited only by one’s desire to do so, there is significant data to back up this belief, with Japanese and Korean frequently appearing on lists of the “Most Difficult Languages to Learn” published by linguists and educational websites.

Do not be discouraged, though! Learning either of these languages is entirely possible. It just may take a bit longer compared to languages like Spanish, which are more similar to English.

left: «Japanese language» written in Japanese

right: «Korean language» written in Korean

But this does raise the question: Which is more difficult to learn, Japanese or Korean?

Japanese versus Korean learning difficulty

The United States Foreign Service Institute has a difficulty ranking system for languages, and it works in much the same way that categorizing hurricanes does.

The higher the number, the more difficult the language is to learn for native English speakers.

So, where do the Japanese and Korean languages rank? Well, they both score a “4”, which is the highest number a language can have in the Foreign Service Institute’s system.

That means Japanese and Korean are languages with the same difficulty, right? Yes and no. It’s not that simple. Let’s look a little deeper and find out why.

Linguistic differences and similarities between Japanese and Korean

Japanese and Korean use different writing systems and belong to unrelated language families. There is no overlap between the thousand most common Japanese words and the equivalent Korean vocabulary list.

One thing that Japanese and Korean do have in common is that they are not tonal languages. Many other Asian languages are tonal, like Chinese, Thai, and Vietnamese, for example, in which the tone of voice (rising, falling, etc.) can change one word into another.

The writing system is one aspect where Japanese is significantly more difficult than Korean. Japanese simultaneously uses three writing systems called hiragana, katakana, and kanji, where the kanji themselves are borrowed characters from the Chinese languages.

- Hiragana, Japan’s native writing system

- Katakana, used for loan words from foreign languages

- Kanji (Chinese characters)

All of these symbols are pronounced with the same spoken syllables, but the written words differ quite a bit visually.

Here is, for example, the word for “Japanese language” written in the three different writing systems:

| System | Japanese | Romaji | Characters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hiragana | にほんご | nihongo | に ni, ほ ho, ん n, ご go |

| Katakana | ニホンゴ | nihongo | ニ ni, ホ ho, ン n, ゴ go |

| Kanji | 日本語 | nihongo | 日 ni, 本 hon, 語 go |

In contrast to Japanese, the Korean language has a single writing system called Hangul, composed of 19 consonants and 21 vowels. This writing system creates syllabic blocks read from left to right (similar to English), but also from top to bottom within those same syllables.

For example, here is how the word for “Korean language” is written in Hangul: 한국어 (hangugeo)

Each individual syllable in this example is pronounced as follows:

| syllable | pronunciation |

|---|---|

| 한 | (han) |

| 국 | (gug) |

| 어 | (eo) |

More specifically, each part within each syllable corresponds to its own letter like so:

| Korean | English |

|---|---|

| ㅎ | h |

| ㅏ | a |

| ㄴ | n |

| ㄱ | g |

| ㅜ | u |

| ㅓ | eo |

| ㅇ | silent |

From a reading and writing standpoint, Japanese is much more difficult to learn compared to Korean simply because of its many writing systems and the fact that there are thousands of kanji to memorize.

Korean writing, while perhaps confusing at first, can theoretically be learned to a level of basic understanding within a couple of days.

Korean Grammar vs. Japanese Grammar

Now, before jumping to conclusions and deciding that Korean is the easiest of the two, let’s look at some actual sentences and understand how the grammar differs.

Fortunately, as a general rule, Japanese and Korean each follow a subject-object-verb (SOV) order.

English, on the other hand, prefers the subject-verb-object (SVO) way of doing things, which means learners coming from this language may experience some trouble adjusting.

Here’s the same sentence in each language for comparison:

- English: I am studying English.

- Japanese: 私は英語を勉強しています。(watashi wa eigo o benkyou shiteimasu.)

- Korean: 나는 영어를 공부하고 있습니다. (naneun yeong-eoleul gongbuhago issseubnida.)

It may be difficult to see the distinct words at first if you don’t already read some Japanese or Korean, but for those whose understanding comes from an SVO language like English, each sentence reads something like this: “I, English, am learning.”

Which can be quite hard to comprehend at first. Unfortunately, things only become more and more difficult as one’s learning progresses deeper into either language and grammar concepts get more complicated.

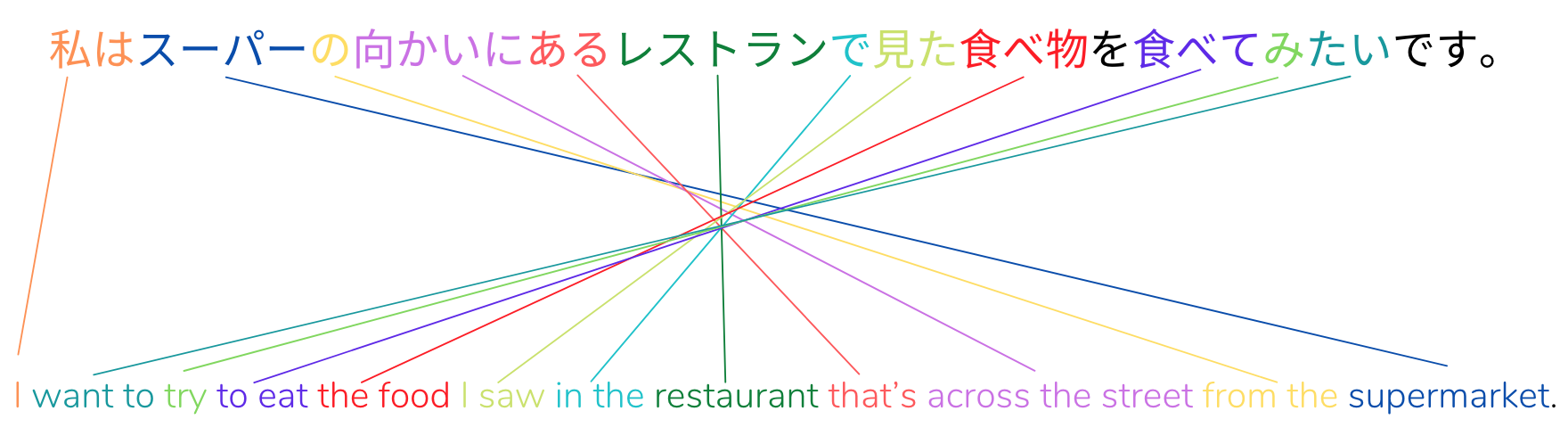

Here’s what a fully complex sentence could look like in Japanese, with its corresponding grammatical phrases pointed out in English:

Of course, because they are unique languages, the grammatical structures between the two aren't always exactly the same at all times. However, for the most part, it can be said that Japanese and Korean are equally tough grammar-wise.

Korean Pronunciation vs. Japanese Pronunciation

When it comes to pronunciation, Korean is harder than Japanese (especially for beginners).

The Japanese language has 5 vowels. The pronunciation of these vowels stays the same, no matter what other consonant or vowel they happen to be paired with.

Here are the 5 Japanese vowels together with their pronunciation:

| Hiragana | English | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| あ | a | pronounced like the “a” in «caw» |

| い | i | pronounced like how we say “e” by itself as a letter |

| う | u | pronounced like the “oo” in «cool» |

| え | e | pronounced like the “e” in «enter» |

| お | o | pronounced like the “o” in «order» |

So, with the other hiragana symbols, there may be:

- か hiragana ‘ka’ - pronounced like “ca” in «caw».

- き hiragana ‘ki’ - pronounced almost exactly like «key».

- く hiragana ‘ku’ - pronounced like “coo” in «cool».

- け hiragana ‘ke’ - pronounced like “ke” in «ketchup».

- こ hiragana ‘ko’ - pronounced like “co” in «coach».

This illustrates how even when the hiragana symbol is different and has a different overall pronunciation, the specific sounds of the same vowels never change. In this way, at least with hiragana and katakana, there is almost never any guesswork needed to correctly pronounce any word in Japanese.

Japanese Kanji characters can be more difficult to read because they often have multiple different readings. But even then the individual spoken syllables are still always the same as those found in hiragana and katakana. This makes conversation easier.

Here’s an easy example:

« 青い » is the kanji for “blue”, and it is pronounced with the hiragana symbols « あおい ».

And even though the word is composed of 3 spoken vowels in a row, none of those vowels change in pronunciation so the way to say the word is exactly as one would expect - “Aoi” - per the guidelines above.

Korean, in contrast, has 8 simple vowels and 13 complex vowels. Simple vowels are just single letters, whereas complex vowels are two simple vowels combined to create a new sound.

If that seems extremely complicated, don’t worry because it’s honestly not too different from what is already done with English.

Here are the 8 simple Hangul vowels:

- ㅏ ‘a’ - pronounced almost exactly like “ah.”

- ㅓ ‘eo’ - pronounced like “u” in «fun».

- ㅗ ‘o’ - pronounced like “o” in «snow».

- ㅜ ‘u’ - pronounced like “oo” in «spoon».

- ㅣ ‘i’ - pronounced like “ea” in «leak».

- ㅡ ‘eu’ - pronounced like “oo” in «brook».

- *ㅐ ‘ae’ - pronounced like “a” in «bat».

- *ㅔ ‘e’ - pronounced like “e” in «met».

*These days, native speakers of Korean often don’t recognize much of a distinction between these two vowel sounds.

The complex vowels in Korean generally fall into 1 of 2 categories. One is where the simple vowel sound is combined with another sound similar to ‘y’ like so:

- ㅑ ’ya’ - pronounced like “ya” in «yawn».

- ㅕ ’yeo’ - pronounced like “yu” in «yummy».

- ㅛ ‘yo’ - pronounced like “yo” in «yogurt».

- ㅠ ‘yu’ - pronounced almost exactly like «you».

- ㅒ ’yae’ - pronounced like “ya” in «yam».

- ㅖ ‘ye’ - pronounced like “ye” in «yesterday».

And the other is where the simple vowel is combined with a ‘w’ like this:

- ㅘ ‘wa’ - pronounced like “wa” in «wander».

- ㅚ ‘oe’ - pronounced like “wa” in «wait».

- ㅙ ‘wae’ - pronounced like “wha” in «whack».

- ㅝ ‘wo’ - pronounced like “wo” in «won».

- ㅟ ‘wi’ - pronounced almost exactly like the word «we».

- ㅞ ‘we’ - pronounced like “we” in «wet».

- *ㅢ ui - pronounced like the “wei” in «weiner».

(*is a bit of a unique vowel that doesn’t quite fit in the previous two groups).

This being the case, it becomes clear how Korean is harder than Japanese when it comes to pronouncing distinct words correctly. And once again, things only get more complicated once consonants are added into the mix.

It’s unnecessary to go over each and every Korean consonant at this time, but here’s a quick example to explain some of the pronunciation “rules” that may appear:

« ㅁ » is the consonant ‘m’ and it is generally pronounced like the “m” in “map” when it starts at the beginning of a word.

« ㄱ » is the consonant ‘k’ and it is generally pronounced like the “k” in “Kyle.” However, when it occurs at the beginning of a syllable, it sounds more like the “g” in “go.” Despite that, when it appears once again at the end of a word, it goes back to making a “k” sound.

So for example, the Korean word « 미국 » (the word for “United States of America”), is pronounced “mi guk” NOT “mi gug.”

It’s a lot to think about, especially when considering the fact that Korean Hangul still has 17 other consonants remaining and they each have their own unique pronunciation rules.

Speaking Politely in Japanese and Korean

For most English speakers, being polite generally just means saying things like “please,” and “thank you,” and “May I?” With Japanese and Korean though, polite speech is almost like a completely different language within the language.

Plus, to make matters even more challenging for the foreign learner, the correct polite phrases and words needed completely depend on who is talking to whom.

If you truly want to learn to speak and understand either of these languages, it is entirely necessary to at least be familiar with their formal and informal manners of speaking. Let’s start with Japanese first.

Levels of Formality in Japanese

It’s not easy to give an exact number of levels of formal speech in Japanese, but generally, most people agree that there are three:

- 丁寧語 (ていねいご/teineigo)

- くだけた にほんご (kudaketa nihongo)

- 敬語 (けいご/keigo)

Another thing worth mentioning is the existence of gendered Japanese language: «danseigo» (masculine language) and «joseigo» (feminine language)

Japanese Polite Language: Teineigo

When beginners first start learning Japanese, this is where they typically begin as it’s the most standard way of speaking.

This polite language is used primarily between people who are strangers to one another, have no particular relationship, or are coworkers. It is also the default language for speaking to someone of higher rank.

We have a full article on Japanese etiquette and phrases for business, if you would like to learn more about this.

Here are two example phrases you might hear at this level of polite speech:

- すみません、これは醬油ですか?

(sumimasen, kore wa shoyu desu ka? / Excuse me, is this soy sauce?) - 私は毎朝30分走ります。

(watashi wa mai asa san juu bu hashiri masu / I run for 30 minutes every morning)

Teineigo is almost always distinguishable by all of its sentences having the ending suffixes of “です/desu" for nouns and “ます/masu” for verbs, as they are necessary to communicate formality in Japanese. Just as well, the honorifics of “お/o” and “ご/go” will appear before certain words and phrases to emphasize politeness like so:

- お名前は?

(o namae wa? / What is your name?) - ご注意ください

(go chui kudasai / Please be careful)

Japanese Honorific Language: Keigo

Keigo is even more polite than teineigo and it is always used in highly formal situations, especially when the other individual or individuals are of significantly higher rank.

This sort of language is particularly noticeable during public announcements and when company employees are speaking to their customers.

For example, these are some things you may hear when walking into a restaurant in Japan:

- いらっしゃいませ!

(irasshaimase! / Welcome! Please come in!) - ここでは少々お待ちください

(koko dewa shosho omachi kudasai / Please wait here for a little while)

It is also very common to see extra conjugations to the “です/desu" and “ます/masu” sentence enders. These conjugations don’t actually change any meaning of the sentence. They only serve to heighten the politeness even further. Here’s a simple example:

- よろしくお願いします (yoroshiku onegai shimasu) which can translate to many things, but is generally used when making requests, would instead become よろしくお願い致します (yoroshiku onegai ita shimasu).

Japanese Casual/Informal Language: kudaketa nihongo

Finally, there is the style of speaking that is most commonly used between family, close friends, and perhaps between strangers at an izakaya (Japanese bar) who have had a bit too much to drink together.

With casual Japanese, the same principles of grammar still apply, but they are much less strict. Likewise, particles like は/ha and を/o are frequently tossed aside for the sake of conversational ease.

Just be sure to be very careful as this type of language should never be used in anything resembling a professional situation or directed towards those of higher social rank:

- それなんだよ?

(sore nanda yo? / What the heck is that?) - おい、君のアイスちょうだい

(oi, kimi no aisu chodai / Hey, gimme your ice cream.) - 待って、待って!

(matte, matte! / Wait, hold up! )

On a related note, we have an article on Japanese phrases for making Japanese friends.

Levels of Formality in Korean

Compared to Japanese, Korean has more than twice the number of polite speech levels. Seven to be exact! It would take quite a while to go over each one in complete detail, but let’s briefly go over what they are in order of descending formality.

1. 하소서체 Hasoseo-cheThis is the absolute highest level of formal speech. These days, it is almost never heard in actual conversation simply because it is specifically used for addressing those of royalty or similar stature.

As such, it’s mostly heard in televised historical dramas, or read in religious texts or similar documents.

It is often marked by the sentence ender -나이다 (-naida).

2. 하십시오체 Hasipsio-cheA very respectful form of speech similar to Japanese Keigo. In Korea, this is the sort of language heard during public announcements, business discussions, and service industry interactions. This is the correct way to speak to strangers and those of higher rank.

It is often marked by the sentence ender –ㅂ니다 (-bnida).

3. 하오체 Hao-cheUnlike hasoseo-che and hasipsio-che, hao-che is used more specifically for speaking to those of the same, or lower, social rank. As such, it should not be used with those who rank higher than oneself.

It is often marked by the sentence enders –소/-오 (-so / -o).

4. 하게체 Hage-cheHage-che is similar to hao-che in that it is used often for speaking to those of lower rank, except that it is never used when speaking to children. However, it is also considered a bit outdated at times and is generally seen mostly in novels.

It is often marked by the sentence ender –네 (-ne).

5. 해라체 Haera-cheThis level of formal speech is where “plain speech” starts to become apparent. With haera-che, there is no additional degree of respect implied, but at the same time it is not considered disrespectful in proper contexts. It can often be seen in newspapers and when describing third-person accounts.

It is often marked by the sentence enders -ㄴ다/-는다 (-nda / -neunda).

6. 해요체 Haeyo-cheHaeyo-che is considered to be informal, but is still also polite at the same time. It is perhaps the most common manner of speaking and as such will be heard in many, everyday situations. Surprisingly to foreign learners of Korean, Haeyo-che is a safe choice when unsure of which level of formality to use with someone else.

It is often marked by the sentence ender –요 (-yo).

7. 해체 Hae-cheFinally, there is hae-che which is highly casual and used between friends, family, and when talking to younger people. Additionally, if one is angry with another individual and truly wishes to be insulting, this is the language he or she would use. It is also called “Banmal” (반말).

It is often marked by the sentence enders –아/-어/-지 (-a / -eo / -ji).

With so many more levels of formality compared to Japanese, it is clear that Korean is harder than Japanese in regard to polite speech.

Granted, becoming comfortable with formal speech of any level in either Japanese or Korean is actually much easier than you might expect. It just takes a little practice, along with genuine apologies when mistakes are inevitably made.

Conclusion

The relative difficulty of learning Japanese versus Korean depends on the desired level of fluency.

Someone who only wishes to reach a conversational level will perhaps find Japanese easier to learn than Korean. There’s less conversational nuance, and you’re less likely to mispronounce new or unique words due to the more basic nature of the syllables used.

But if you want to achieve complete literacy, Japanese could theoretically take a lifetime to master. Even native Japanese speakers sometimes forget how to correctly write some of the rarer kanji, so it’s no surprise that foreigners struggle to a greater degree.

The path to Korean literacy may offer more consistent gratification, even if complete mastery of the grammar may take much longer.

No matter which direction you decide to go, either language is an entirely worthwhile endeavor. And once you have any level of mastery, a whole new world filled with unique cultural experiences and friendships will be available to you.