Chinese and Japanese: language similarities and differences

A basic greeting like “hello” is “こんにちは” (Konnichiwa) in Japanese and “你好” (Nǐ hǎo) in Chinese. They don’t look very similar, do they?

But comparing two languages just on a basic greeting is quite limited. Let’s look at a full sentence:

| English | Is Japanese similar to Chinese? |

|---|---|

| Japanese | 日本語は中国語に似ていますか? |

| Chinese | 日語和漢語相似嗎? |

Now we see some similarities. The Japanese and Chinese versions of this sentence have some characters in common (‘日’, ‘語’, and ‘似’). But where do these similarities come from?

Japan is less than 500 miles away from China. That’s roughly four times the distance between Japan and Korea, but it’s about half the distance between New York City and Miami, Florida.

As shipbuilding techniques progressed, Chinese and Japanese cultures started to interact, and so did their languages.

The first documented interaction between Japan and China dates back to the 1st century CE. That’s the period when, halfway across the globe, the Roman Empire was expanding its control of most of the Mediterranean.

Chinese and Japanese are not related languages. They belong to different language families. However, they do have some similarities because their interactions have led to the borrowing of some features (in particular, the use of Chinese characters in Japanese).

When we look at the list of the most common Japanese words, we notice that many of them contain Chinese characters. This is one of the most striking similarities between the two languages.

In Japanese, these characters are called Kanji; in Chinese, they are called Hanzi.

But remember the Japanese greeting “こんにちは” (Konnichiwa). Those aren’t Chinese characters.

While Chinese is written entirely with Chinese characters, Japanese uses two additional scripts alongside its Chinese characters. These two scripts are called Hiragana and Katakana, and they are syllabaries (each symbol represents a syllable).

Chinese and Japanese belong to separate language families; they do not descend from a common ancestor language.

Chinese is in the Sino-Tibetan language family, together with languages such as Tibetan and Burmese. Japanese, on the other hand, belongs to the Japonic language family, which includes, besides Japanese, the Ryukyuan languages spoken in the Ryukyu Islands of Japan.

Similar words

Because Japanese uses Chinese characters, some vocabulary words are spelled the same in both languages. However, in most cases, the pronunciation of these common words differs widely between the two languages.

| English | Chinese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|

| mountain | 山 (Shān) | 山 (Yama) |

| hand | 手 (Shǒu) | 手 (Te) |

| water | 水 (Shuǐ) | 水 (Mizu) |

| flower | 花 (Huā) | 花 (Hana) |

| rain | 雨 (Yǔ) | 雨 (Ame) |

| fire | 火 (Huǒ) | 火 (Hi) |

| light | 光 (Guāng) | 光 (Hikari) |

| day | 日 (Rì) | 日 (Hi) |

| forest | 森林 (Sēnlín) | 森林 (Shinrin) |

| cat | 猫 (Māo) | 猫 (Neko) |

| year | 年 (Nián) | 年 (Toshi) |

| food | 食物 (Shíwù) | 食物 (Shokumotsu) |

| world | 世界 (Shìjiè) | 世界 (Sekai) |

| life | 生活 (Shēnghuó) | 生活 (Seikatsu) |

| school | 学校 (Xuéxiào) | 学校 (Gakkō) |

| student | 学生 (Xuéshēng) | 学生 (Gakusei) |

| freedom | 自由 (Zìyóu) | 自由 (Jiyū) |

| happiness | 幸福 (Xìngfú) | 幸福 (Kōfuku) |

Simplified characters

China has implemented significant simplifications to Chinese characters, while in Japanese, the simplification of characters has been more limited.

| English | Japanese | Chinese Traditional | Chinese simplified |

|---|---|---|---|

| wind | 風 (Kaze) | 風 (Fēng) | 风 (Fēng) |

| horse | 馬 (Uma) | 馬 (Mǎ) | 马 (Mǎ) |

| bird | 鳥 (Tori) | 鳥 (Niǎo) | 鸟 (Niǎo) |

| cloud | 雲 (Kumo) | 雲 (Yún) | 云 (Yún) |

| bridge | 橋 (Hashi) | 橋 (Qiáo) | 桥 (Qiáo) |

| mother | 母親 (Hahaoya) | 母親 (Mǔqīn) | 母亲 (Mǔqīn) |

| sun | 太陽 (Taiyō) | 太陽 (Tàiyáng) | 太阳 (Tàiyáng) |

| knowledge | 知識 (Chishiki) | 知識 (Zhīshì) | 知识 (Zhīshì) |

| warehouse | 倉庫 (Sōko) | 倉庫 (Cāngkù) | 仓库 (Cāngkù) |

Historically, only a small fraction of the Chinese population could read and write, as those skills required memorizing thousands of characters, many of which are complicated. To improve the literacy rate, the Chinese government introduced a simplified form of Chinese characters during the 1950s.

Today, there are two forms of Chinese characters: Traditional Chinese characters (used in Taiwan and Hong Kong) and Simplified Chinese characters (used in China and Singapore).

The Japanese language had borrowed Chinese characters centuries before this simplification took place. As a result, the Japanese Kanji tend to be closer to the traditional Chinese characters than the simplified ones.

(Japan did have its own orthographic reforms but those simplifications do not coincide with the spelling reforms in China).

Different word order

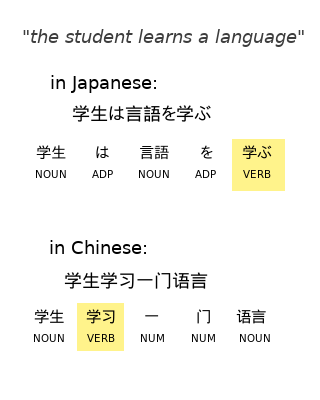

An interesting grammatical difference between Japanese and Chinese is the ordering of words in sentences. In Japanese sentences, the verb often goes at the end. Linguists classify Japanese as an SOV (subject-object-verb) language.

In contrast, Chinese is an SVO (subject-verb-object) language.

The following diagram illustrates this difference in word order by representing the same English sentence translated into both Japanese and Chinese.

This example also showcases a similarity between Chinese and Japanese that adds a extra bit of difficulty for those learning these languages: in both Chinese and Japanese writing, there are typically no spaces separating the different words in a sentence.

Differences in pronunciation

While there are said to be over 50,000 hanzi in existence, most modern dictionaries only include around 20,000, and the average educated Chinese adult knows around 8,000 of them. For daily use, however, many Chinese language learners find they need only 2,000-3,000 hanzi to comfortably navigate their daily life in a Chinese-speaking country such as China or Taiwan.

The reason for the Chinese language having so many different characters is that each one represents a single object or concept, and the pronunciation is static to that character.

For example, the character « 水 » means “water” and is pronounced 'shuǐ '. On its own, the character means “water”, but when coupled with the character « 星 » meaning “star” and pronounced 'xīng', it becomes « 水星 » which means “mercury” and is pronounced 'shuǐxīng'.

Even when coupled with another character to take on a whole new meaning, the pronunciation does not change (with some exceptions), and the word is represented by those two characters as a whole.

In Japanese, on the other hand, each character has between three and seven pronunciations depending on how the characters are coupled with each other.

Using the previous example, in Japanese, the character « 水 » is pronounced 'Mizu' and still means “water”. Likewise, on its own, the character « 星 » is pronounced 'Hoshi' and means “star”. However, when these characters are combined to form the word for “mercury,” the pronunciation becomes 'suisei,' which is entirely different from the individual pronunciations.

Unfortunately, there is no real way to tell how each kanji will be pronounced other than memorization.

Unlike Japanese, Chinese is a tonal language

Another key difference between Japanese and Chinese is the range of sounds. Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language with four tones and 67 possible phonemes. The tone affects the meaning of the word, so it is vital to get it correct, which is a challenging point for many non-native speakers.

For example: mā (妈 ), má (麻), mǎ (马), and mà (骂). Although they all sound quite similar to the untrained ear, their meanings greatly differ. Respectively they mean "mother", "hemp", "horse", and "scold".

Japanese, on the other hand, has 107 possible sounds, which sound like a lot until you take into account that they are just variations of a basic (a, i, u, e, o) vowel pattern with consonant variations.

Moreover, from the standpoint of an English speaker, Japanese pronunciation is generally considered easier compared to Chinese due to the absence of tones.

The Japanese language has three writing systems

As Japan started to develop and grow as a country, it started to look east to China as a Mecca of culture, society, and knowledge.

With over 5,000 years of history, China had quite the headstart on Japan when it came to things such as a written system for their language and so rather than make their own, during the 4th century, the Japanese simply borrowed the Chinese written hanzi system and adapted it to their language using Japanese pronunciations.

This is why many loanwords from Chinese and word stems are written using Chinese characters called kanji.

- 漢字 - Kanji - Chinese Characters (kanji)

- 図書館 - Toshokan - Library

- 農場 - Noujou - Farm

At the time, however, only the aristocratic elite had the time, money, and resources to learn how to read all those characters, and even if you were among the privileged, only men were permitted to learn how to read Chinese characters.

For this reason, during the 9th century, court women were said to have developed a phonetic system of writing known as hiragana to simplify Chinese characters and make them more accessible.

That is why words originating from Japan and grammatical components are written using hiragana today.

- こんにちは - Konnichiwa - Hello

- ありがとう - Arigatou - Thank you

- すみません - Sumimasen - Sorry

Katakana, the 3rd writing system used in Japanese, was also developed during this period by Buddhist monks who used it to help students and scholars learn how to read Chinese characters. Today, Katakana is used for writing foreign words that entered the Japanese language.

- ロボット - Robotto - Robot

- ピザ - Piza - Pizza

- シャツ - Shatsu - Shirt

Traditional versus simplified Chinese characters

During the modernization period of China between 1949 and 1964, the Chinese communist party of mainland China introduced a simplified system of characters to increase the literacy rate.

This period is linked with the Chinese Civil War (1929-1949), during which the traditionalists of the Kuomintang party sought to maintain Chinese traditions and customs, hence hanging on to the "traditional" Chinese hanzi system.

So are they really so different? Many common characters are shared between the two writing systems such as 是 (shì), 中 (zhōng), and 水 (shuǐ). Other characters only have minor differences such as 为 (wèi) in simplified and 為 (wèi) in traditional.

Finally, some characters are absolutely different. Take 'ràng', for example, which is « 让 » in simplified and « 讓 » in traditional. You can understand why people felt the need for simplification when you consider the character for “turtle” ('guī'), which is « 龟 » in simplified and « 龜 » in traditional.

Are Japanese and Chinese Mutually Intelligible?

In short, no. When spoken, Japanese and Mandarin Chinese speakers cannot understand each other at all apart from potentially some loanwords that might make it through.

However, since both languages do use hanzi/kanji in their written languages, often portions of written text such as menus can be read or vaguely understood.

Consider, for example, "牛肉麵" (niúròu miàn), a beef noodle soup, which is a specialty dish in Taiwan. While this Chinese term is not common in Japan, a Japanese speaker would recognize the parts "牛肉" (pronounced 'gyuniku' in Japanese) meaning "beef" and "麵" (men) which means "noodle" in Japanese as well. From the context, they could figure out the meaning.

One difference between Japanese and Chinese is that Japanese incorporates many loanwords from English. This presence of English loanwords helps reduce the number of new words that need to be memorized when studying the Japanese language.

| English | Chinese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|

| radio | 收音机 (Shōuyīnjī) | ラジオ (Rajio) |

| cheetah | 猎豹 (Lièbào) | チーター (Chītā) |

| Sweden | 瑞典 (Ruìdiǎn) | スウェーデン (Suuēden) |

| America | 美国 (Měiguó) | アメリカ (Amerika) |